A minefield of attractor states

In this post, I articulate my version of Holden Karnofsky's thesis that we could be living in the most important century, with an emphasis on why this century's level of influence is distinct. If you've not read the series, and find the claims in this post to be absurd, then I highly recommend checking out (at least) the summary and the post All Possible Views About Humanity's Future Are Wild.

My argument is (roughly):

humanity falling into an 'attractor state' is very significant,

the more influence we have over that possibility, the more important this era is, and

this seems to be the case, moreso than ever.

What makes a particular era important?

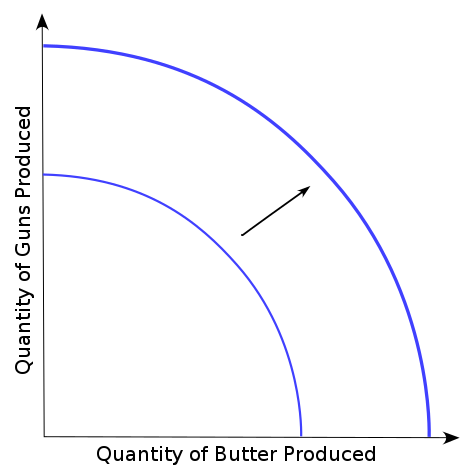

In the series, Karnofksy discusses technologies that are on our horizon, how they will transform humanity, and how unreasonable it is that almost nobody seems to care. Living through a technological revolution is not, however, unprecedented. Wikipedia has a nice list of intellectual, philosophical, and technological revolutions which includes the Upper Neolithic Revolution, the First Industrial Revolution, and this figure demonstrating how technological progress means we can shoot our butter and eat it too:

Designating a single era as the most decisive is tricky, of course, but focusing on revolutions makes sense. Discontinuous changes like technological innovations (a 0 → 1 change) seem more impressive and significant than the subsequent propagation and advancement of those technologies (1 → n changes). For example, the creation of useful steam engines (0 → 1) seems more notable than the subsequent improvements and scaling of our power generation (1 → n), despite the latter accounting for significantly more economic activity and impacted lives.

This is easily justified since the value accrued from 1 to n can just be attributed to those who went from 0 to 1 in the first place. But that logic leads you to the trivial conclusion that no era is particularly important, as it fully depends on the shifts that came before it (from human evolution, to the emergence of life, to the birth of the universe). Everything we do is (1) defined by the past and (2) defines the future; this is quite normal.

Importance ≈ expected impact - the counterfactual

But I don't think 0 → 1 events are impressive just because they are the start of something big. They're impressive because the value of their counterfactuals — the circumstances in which the event didn't take place — would have been predictably different. While many unprecedented events seem inevitable in retrospect, their timing and expected impact are not predetermined.

For example, the smallpox vaccine was created in 1798, but the virus remained widespread for the next century-and-a-half, with 50 million cases occurring each year in the early 1950s. In 1958, Viktor Zhdanov initiated a campaign to eradicate smallpox; he convinced the World Health Assembly to undertake this challenge when no disease had ever been eradicated before. A few years before this, the Assembly had rejected a similar proposal because it was (understandably) deemed too unrealistic. But thanks to Zhdanov's determination, the Assembly took on the challenge.

By 1979 the programme had succeeded. The virus that killed 500 million people was gone.

How long would it have been before someone had both the expertise and the initiative to successfully set a campaign like that in motion? And with 300 million dying in the 20th century alone, all delays are devastatingly tragic.

In contrast, if the organisms at the start of our evolutionary lineage had never formed, life (in all likelihood) would have evolved from some other H-dependent autotrophs (or whatever) within the next billion years, since the conditions for such an event to occur were set up. Slight deviations in the origins of life change everything, but not in any predictable way. There's little ex ante reason why any one starting point would be better or worse than another. Of course, ex post, I'm glad things went how they did (otherwise we wouldn't be here), but the value of future evolved species cannot be straightforwardly inferred from the composition of the chemical soups that microorganisms self-assembled in.

This is related to cluelessness; every decision (regardless of its perceived significance) will lead to consequences that will completely alter the future state of the universe. However, in most instances, the expected change in the value of the long-run future is distributed symmetrically around zero, for whichever decision you take.

With this thinking, the emergence of technological maturity doesn't necessarily make the preceding decisions important, since the most significant counterfactuals may have been ruled out a long time ago. So, if we live at the hinge of history, it doesn't make this time the most important by default. Maybe our only task is to open the door.

Are the actions we take over the next century plagued by moral cluelessness? Or, like eradicating smallpox, can we make choices that are clearly, massively good for the world?

Choices during technological transitions don't usually have persistent effects

Holden Karnofsky (reasonably) believes the next technological transition will change everything. If the future involves transitioning to digital life, he claims that the nature of our transition will have a lasting influence:

acceptably good initial conditions (protecting basic human rights for digital people, at a minimum), plus a lot of patience and accumulation of wisdom and self-awareness we don't have today (perhaps facilitated by better social science), could lead to a large, stable, much better world. It should be possible to eliminate disease, material poverty and non-consensual violence, and create a society much better than today's.

You could imagine a (particularly visionary) person saying that about the industrial revolution, but I don't think the initial conditions mattered that much in the long run. It would have been wrong to claim that actions taken during that period of time would lock our society into a certain set of values. You could argue that the amount of capital and power that a small set of people accumulated put us on a narrow path that we cannot escape from, but I'm not convinced. As Dwarkesh Patel puts it in This Can Go On:

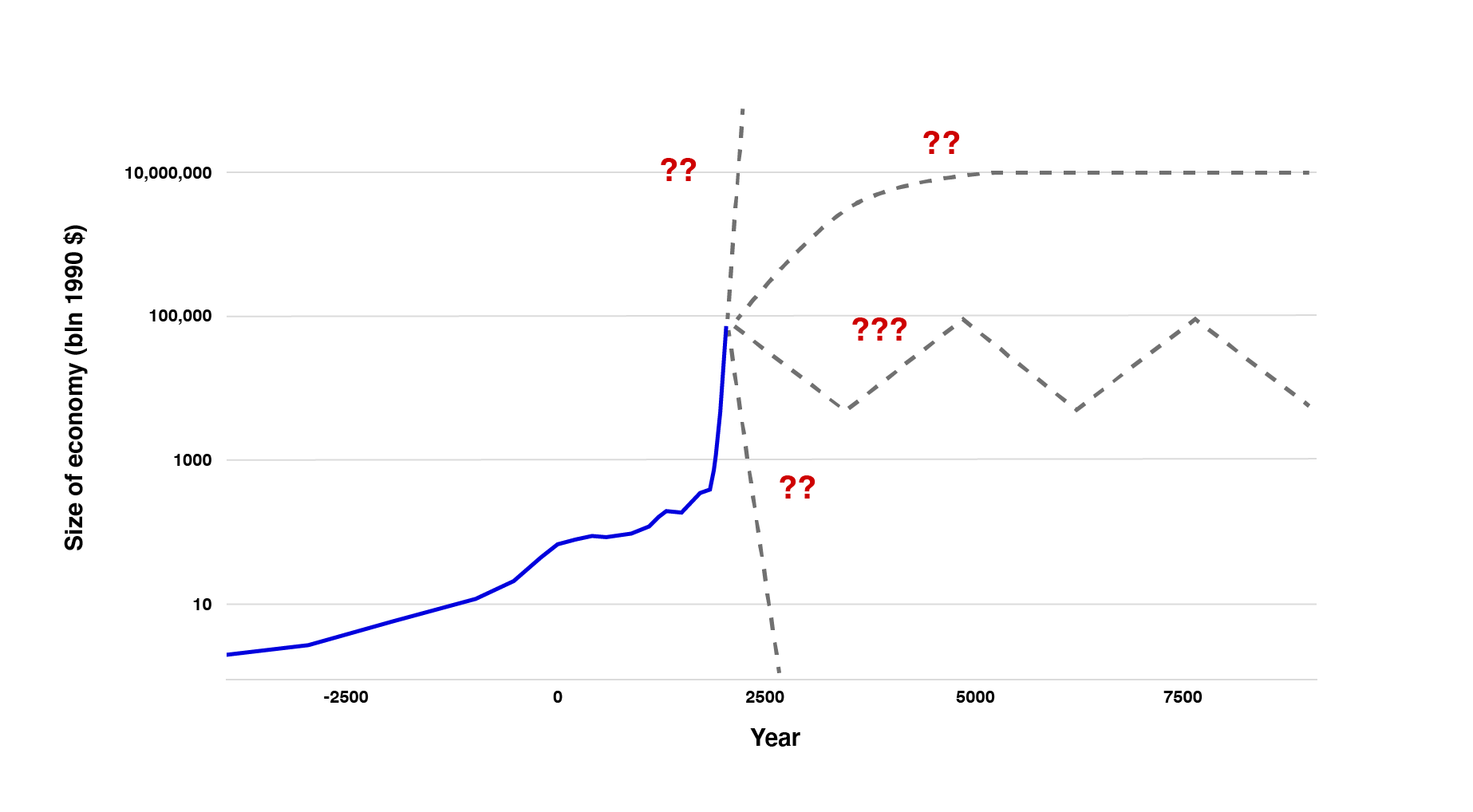

The development of the printing press resulted in wars, revolutions, religions, political movements, and further scientific and technological advances which have completely remade the world. In the simmer scenario [0.2% growth a year for 25,000 years], a technology as fundamental as that is being developed every 500 years for the remainder of our time in the galaxy. In this scenario, no century ends up having extraordinarily important technological changes in the grand scheme of things.

But maybe, if the technologies were more transformative and the transition more discontinuous, the users of the first printing presses would have entirely determined humanity's subsequent trajectory. Karnofsky claims that this may be the case now:

During the century we’re in right now, we will develop technologies that cause us to transition to a state in which humans as we know them are no longer the main force in world events. This is our last chance to shape how that transition happens.

In other words, this transition is different because it won't just induce change, but may eternally restrict humanity's capacity for it. This is a strong claim but, if the future holds a large number of digital people, it is hard to dispute Karnofsky's reasoning. Just a couple of transformative technologies (artificial intelligence and digital consciousness) could lead to human extinction or a permanent, galaxy-wide, dystopian regime — both examples of 'attractor states'.

Why it looks different this time: a minefield of attractor states

The human race’s prospects of survival were considerably better when we were defenceless against tigers than they are today, when we have become defenceless against ourselves.

An attractor state is a condition where, once you enter it, you cannot escape — like a black hole. As Greaves and MacAskill put it: "The non-existence of humanity is a persistent state par excellence. To state the obvious: the chances of humanity re-evolving, if we go extinct, are minuscule".

Extinction scenarios

Take a look at these forecasts on how likely it is that various global catastrophes kill over 95% of the human population (and see this notebook for background information):

A 'catastrophe' in these instances refers to an event that kills 10% of the world's population. The Metaculus community places a 66% chance of this kind of event taking place this century, with AI (the most severe threat) being involved in ~25% of them.

Being able to wipe ourselves out this easily is an incredibly new phenomenon; the concept of humanity being rendered extinct by their own discoveries became salient last century with the invention and proliferation of nuclear weapons. But, if a nuclear catastrophe kills 10% of the population (which is deemed to be roughly as likely as an AI, biological, or 'other' catastrophe doing the same), the likelihood that it kills 95% of the population is significantly lower:

All of these probabilities are unacceptably high, and the severity of these risks is much worse than most people account for. This scenario makes our century uniquely dangerous and, since there's still so much we can do to reduce them, uniquely important.

Non-extinction scenarios

In The Precipice, Toby Ord uses the term 'existential catastrophe' to describe humanity "getting locked into a bad set of futures". Among these bad futures, Ord includes an ‘unrecoverable dystopia’: “a world with civilization intact, but locked into a terrible form, with little or no value”. This would be deemed to be an ‘attractor state’ of significantly lower expected value than alternative possible futures, alongside human extinction.

So if we succeed at avoiding extinction, things could still go horribly wrong. Karnofsky and Ord articulate how and why unrecoverable dystopias may arise, but the number of paths to such an attractor state seems more numerous than you'd initially guess.

For example, to avoid extinction scenarios, humanity may choose to install some stable, global, safety-enhancing regime, as described by Nick Bostrom in the vulnerable world hypothesis. This flavour of attractor state doesn't give me much hope, sadly. For something as totalizing and irreversible as locking in a world government, I would want infeasible levels of certainty about how good it will be.

But, within this minefield of attractor states, not all of them must be entered into suddenly.

If humanity spreads across the galaxy — creating civilisations that are disparate and diverse — the chances of our survival in a given millenium may well spring back to ~100%. This, the secured persistence humanity, is its own (more subtle) attractor state.

Getting the transition right

To me, it seems like we're in a position where we can make choices that are genuinely good for the long-run future; reducing the chance of a civilisational catastrophe, at a minimum, seems like an obviously good bet. Beyond that, there are many other attractor states we could increase the chances of — and doing so would be incredibly consequential.

Because of this, I think the 21st century will be unmatched in terms of the variance in the expected impact of our actions since we can knowingly alter the probability distribution of humanity's future trajectories within this incredibly large range:

As we consider how the future should look, we should be wary of most lock-in scenarios. This is obvious when most of the visible attractor states look really bad, but I also think it's unwise to get locked into any path (even if they look good). It may well be our last chance to define the future, but let's be stewards of humanity's existence rather than legacy builders. I'll explain my full reasoning for that in a future post but, for now, I want to tell you why this thesis supports the simulation hypothesis, despite how silly that sounds.